Detective quantum efficiency

The detective quantum efficiency (often abbreviated as DQE) is a measure of the combined effects of the signal (related to image contrast) and noise performance of an imaging system, generally expressed as a function of spatial frequency. This value is used primarily to describe imaging detectors in optical imaging and medical radiography.

In medical radiography, the DQE describes how effectively an x-ray imaging system can produce an image with a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) relative to an ideal detector. It is sometimes viewed to be a surrogate measure of the radiation dose efficiency of a detector since the required radiation exposure to a patient (and therefore the biological risk from that radiation exposure) decreases as the DQE is increased for the same image SNR and exposure conditions.

The DQE is also an important consideration for CCDs, especially those used for low-level imaging in light and electron microscopy, because it affects the SNR of the images. It is also similar to the noise factor used to describe some electronic devices.

Contents |

History

Starting in the 1940s, there was much scientific interest in classifying the signal and noise performance of various optical detectors such as television cameras and photoconductive devices. It was shown, for example, that image quality is limited by the number of quanta used to produce an image. The quantum efficiency of a detector is a primary metric of performance because it describes the fraction of incident quanta that interact and therefore image quality. However, other physical processes may also degrade image quality, and in 1946, A. Rose[1] proposed the concept of a useful quantum efficiency or equivalent quantum efficiency to describe the performance of those systems, which we now call the detective quantum efficiency. Early reviews of the importance and application of the DQE were given by Zweig[2] and Jones.[3]

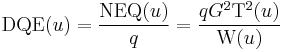

The DQE was introduced to the medical-imaging community by Shaw[4][5] for the description of x-ray film-screen systems. He showed how image quality with these systems (in terms of the signal-to-noise ratio) could be expressed in terms of the noise-equivalent quanta (NEQ). The NEQ describes the minimum number of x-ray quanta required to produce a specified SNR. Thus, the NEQ is a measure of image quality and, in a very fundamental sense, describes how many x-ray quanta an image is worth. It also has an important physical meaning as it describes how well a low-contrast structure can be detected in a uniform noise-limited image by the ideal observer which is an indication of what can be visualized by a human observer under specified conditions.[6][7] If we also know how many x-ray quanta were used to produce the image (the number of x-ray quanta incident on a detector), q, we know the cost of the image in terms of a number of x-ray quanta. The DQE is the ratio of what an image is worth to what it cost in terms of numbers of Poisson-distributed quanta:

.

.

In this sense the DQE describes how effectively an imaging system captures the information content available in an x-ray image relative to an ideal detector. This is critically important in x-ray medical imaging as it tells us that radiation exposures to patients can only be kept as low as possible if the DQE is made as close to unity as possible. For this reason, the DQE is widely accepted in regulatory, commercial, scientific and medical communities as a fundamental measure of detector performance.

Definition

The DQE is generally expressed in terms of Fourier-based spatial frequencies as:[8]

where u is the spatial frequency variable in cycles per millimeter, q is the density of incident x-ray quanta in quanta per square millimeter, G is the system gain relating q to the output signal for a linear and offset-corrected detector, T(u) is the system modulation transfer function, and W(u) is the image Weiner noise power spectrum corresponding to q. As this is a Fourier-based method of analysis, it is valid only for linear and shift-invariant imaging systems (analogous to linear and time-invariant system theory but replacing time invariance with spatial-shift invariance) involving wide-sense stationary or wide-sense cyclostationary noise processes. The DQE can often be modelled theoretically for particular imaging systems using cascaded linear-systems theory.[9]

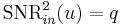

The DQE is often expressed in alternate forms that are equivalent if care is used to interpret terms correctly. For example, the squared-SNR of an incident Poisson distribution of q quanta per square millimeter is given by

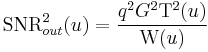

and that of an image corresponding to this input is given by

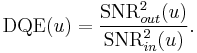

resulting in the popularized interpretation of the DQE being equal to the ratio of the squared output SNR to the squared input SNR:

This relationship is only true when the input is a uniform Poisson distribution of image quanta and signal and noise are defined correctly.

Measuring the DQE

A report by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC 62220-1)[10] was developed in an effort to standardize methods and algorithms required to measure the DQE of digital x-ray imaging systems.

Advantages of high DQE

It's the combination of very low noise and superior contrast performance that allows some digital x-ray systems to offer such significant improvements in the detectability of low-contrast objects - a quality that is best quantified by a single parameter, the DQE. As one medical physics expert recently reported, The DQE has become the de facto benchmark in the comparison of existing and emerging x-ray detector technologies.

DQE especially affects one's ability to view small, low-contrast objects. In fact, in many imaging situations, it's more important to detecting small objects than is limiting spatial resolution (LSR) - the parameter traditionally used to determine how small an object one can visualize. Even if a digital system has very high LSR, it can't take advantage of the resolution if it has low DQE, which prevents the detection of very small objects (Fig. 2).

A study comparing film/screen and digital imaging demonstrates that a digital system with high DQE can improve one's ability to detect small, low-contrast objects – even though the digital system may have substantially lower Limiting Spacial Resolution (LSR) than film.

Reducing radiation dose is another potential advantage of digital x-ray technology; and high DQE should make significant contributions to this equation. Compared with film/screen imaging, a digital detector with high DQE has the potential to deliver significant object-detectability improvements at an equivalent dose, or to permit object detectability comparable to film's at reduced dose.

Equally important, high DQE provides the requisite foundation for advanced digital applications - dual-energy imaging, tomosynthesis, and low-dose fluoro, for instance. Combined with advanced image-processing algorithms and fast acquisition and readout capability, high DQE is key to making such applications as these clinically practical in the years to come.

References

- ^ A. Rose. A unified approach to the performance of photographic film, television pick-up tubes, and the human eye, J Soc Motion Pict Telev Eng 47:273-294, 1946

- ^ H.J. Zweig. Performance criteria for photo-detectors - concepts in evolution, Photo Sci Eng 8:305-311, 1964

- ^ R.C. Jones, Scientfic American 219:110, 1968

- ^ R. Shaw. The equivalent quantum efficiency of the photographic process, J Photogr Sc 11:199-204, 1963

- ^ J.C. Dainty and R. Shaw. Image Science, Academic Press, New York, 1974

- ^ H.H. Barrett, J. Yao, J.P. Rolland and K.J. Myers, Model observers for assessment of image quality, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:9758-9765, 1993

- ^ Medical Imaging - The Assessment of Image Quality, Int Comm Rad Units and Meas, ICRU Report 54, 1995

- ^ I.A. Cunningham, Applied linear-systems theory, in Handbook of Medical Imaging: Vol 1, physics and psychophysics, Ed J. Beutel, H.L. Kundel and R. Van Metter, SPIE Press, 2000

- ^ I.A. Cunningham and R. Shaw, Signal-to-noise optimization of medical imaging systems, J Opt Soc Am A 16:621-632, 1999

- ^ Characteristics of digital x-ray imaging devices - Part 1: Determination of the detective quantum efficiency, International Electrotechnical Commission Report IEC 62220-1, 2003